Kinetic inductance

Kinetic inductance is the manifestation of the inertial mass of mobile charge carriers in alternating electric fields as an equivalent series inductance. Kinetic inductance is observed in high carrier mobility conductors (e.g. superconductors) and at very high frequencies.

Contents[hide] |

Explanation

A change in electromotive force (emf) will be opposed by the inertia of the charge carriers since, like all objects with mass, they prefer to be traveling at constant velocity and therefore it takes a finite time to accelerate the particle. This is similar to how a change in emf is opposed by the finite rate of change of magnetic flux in an inductor. The resulting phase lag in voltage is identical for both energy storage mechanisms, making them indistinguishable in a normal circuit.

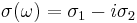

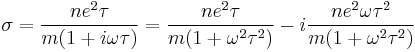

Kinetic inductance ( ) arises naturally in the Drude model of electrical conduction when the relaxation time (collision time)

) arises naturally in the Drude model of electrical conduction when the relaxation time (collision time)  is taken to be non-zero. This model defines a complex conductivity in a time-varying electric field of frequency

is taken to be non-zero. This model defines a complex conductivity in a time-varying electric field of frequency  given by

given by  . The imaginary part arises from kinetic inductance, with

. The imaginary part arises from kinetic inductance, with  . The Drude complex conductivity can be expanded into its real and imaginary components:

. The Drude complex conductivity can be expanded into its real and imaginary components:

where  is the mass of the charge carrier (i.e. the effective electron mass in metallic conductors) and

is the mass of the charge carrier (i.e. the effective electron mass in metallic conductors) and  is the carrier number density. In normal metals the collision time is typically

is the carrier number density. In normal metals the collision time is typically  s, so for frequencies < 100 GHz the term

s, so for frequencies < 100 GHz the term  is very small and can be ignored. Kinetic inductance is therefore only significant at optical frequencies and in superconductors, where

is very small and can be ignored. Kinetic inductance is therefore only significant at optical frequencies and in superconductors, where  .

.

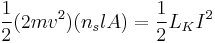

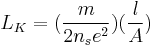

For a superconducting wire, the kinetic inductance can be calculated by equating the total kinetic energy of the Cooper pairs with an equivalent inductive energy:[1]

where  is the electron mass (

is the electron mass ( is the mass of a Cooper pair),

is the mass of a Cooper pair),  is the average Cooper pair velocity,

is the average Cooper pair velocity,  is the density of Cooper pairs,

is the density of Cooper pairs,  is the length of the wire,

is the length of the wire,  is the wire cross-sectional area, and

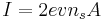

is the wire cross-sectional area, and  is the current. Using the fact that the current

is the current. Using the fact that the current  , where

, where  is the electron charge, this yields:

is the electron charge, this yields:

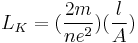

The same procedure can be used to calculate the kinetic inductance of a normal (i.e. non-superconducting) wire, except with  replaced by

replaced by  ,

,  replaced by

replaced by  , and

, and  replaced by the normal carrier density

replaced by the normal carrier density  . This yields:

. This yields:

The kinetic inductance increases as the carrier density decreases. Physically, this is because a smaller number of carriers must have a greater velocity than a larger number of carriers in order to achieve the same current. In a normal metal wire, the resistivity also increases as the carrier density  decreases. As a result, in normal metals the resistive contribution to the impedance dominates the contribution from kinetic inductance up to frequencies ~ THz.

decreases. As a result, in normal metals the resistive contribution to the impedance dominates the contribution from kinetic inductance up to frequencies ~ THz.

Applications

Kinetic inductance in superconductors is exploited to make efficient microwave delay lines as it increases the inductance per unit length of superconducting transmission lines.

Kinetic inductance can be used to make sensitive photon detectors, known as kinetic inductance detectors (KIDs), as the change in the Cooper pair density brought about by the absorption of a photon in a strip of superconducting material produces a measurable change in kinetic inductance.

Kinetic inductance is also used in a design parameter for superconducting flux qubits:  is the ratio of the kinetic inductance of the Josephson junctions in the qubit to the geometrical inductance of the flux qubit. A design with a low beta behaves more like a simple inductive loop, while a design with a high beta is dominated by the Josephson junctions and has more hysteretic behavior.[2]

is the ratio of the kinetic inductance of the Josephson junctions in the qubit to the geometrical inductance of the flux qubit. A design with a low beta behaves more like a simple inductive loop, while a design with a high beta is dominated by the Josephson junctions and has more hysteretic behavior.[2]

See also

References

- ^ A.J. Annunziata et al., "Tunable superconducting nanoinductors," Nanotechnology 21, 445202 (2010), arXiv:1007.4187, doi:10.1088/0957-4484/21/44/445202

- ^ http://books.google.ca/books?id=yOA8rUo5N4oC&pg=PA157 or Cardwell, David A.. Handbook of superconducting materials. London, UK: CRC Press. p. 157. ISBN 0750304324.